Overview

Featured below is a short film of Pam Glick working in her studio and an interview between the artist and Matthew Higgs, Director of White Columns, New York and Founding Curatorial Advisor of Independent

Stephen Friedman Gallery presents two solo exhibitions by American artist Pam Glick for Independent and Frieze New York. The presentations, which will take place one week apart in New York, are both curated by Matthew Higgs, Director of White Columns, New York and Founding Curatorial Advisor of Independent.

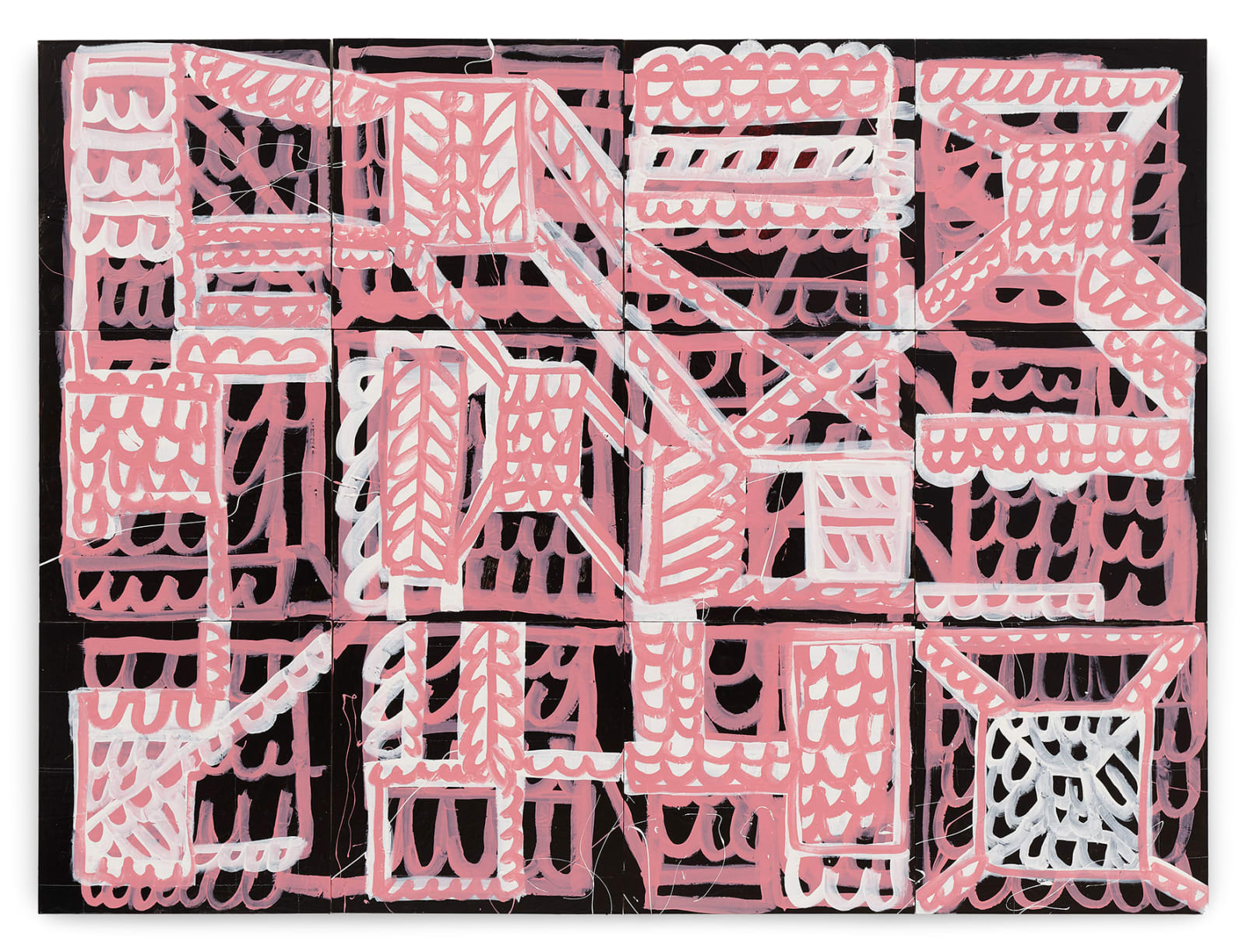

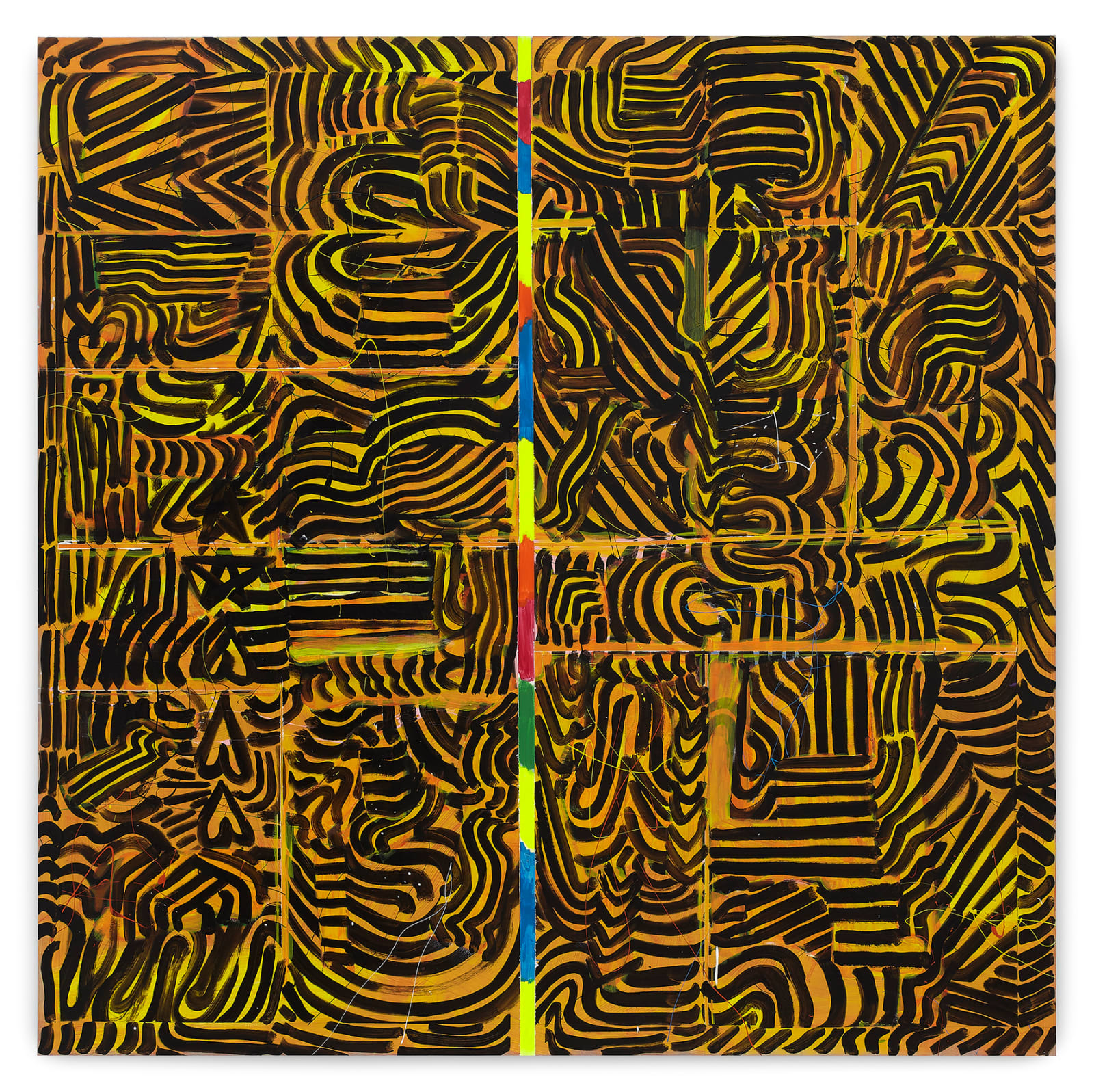

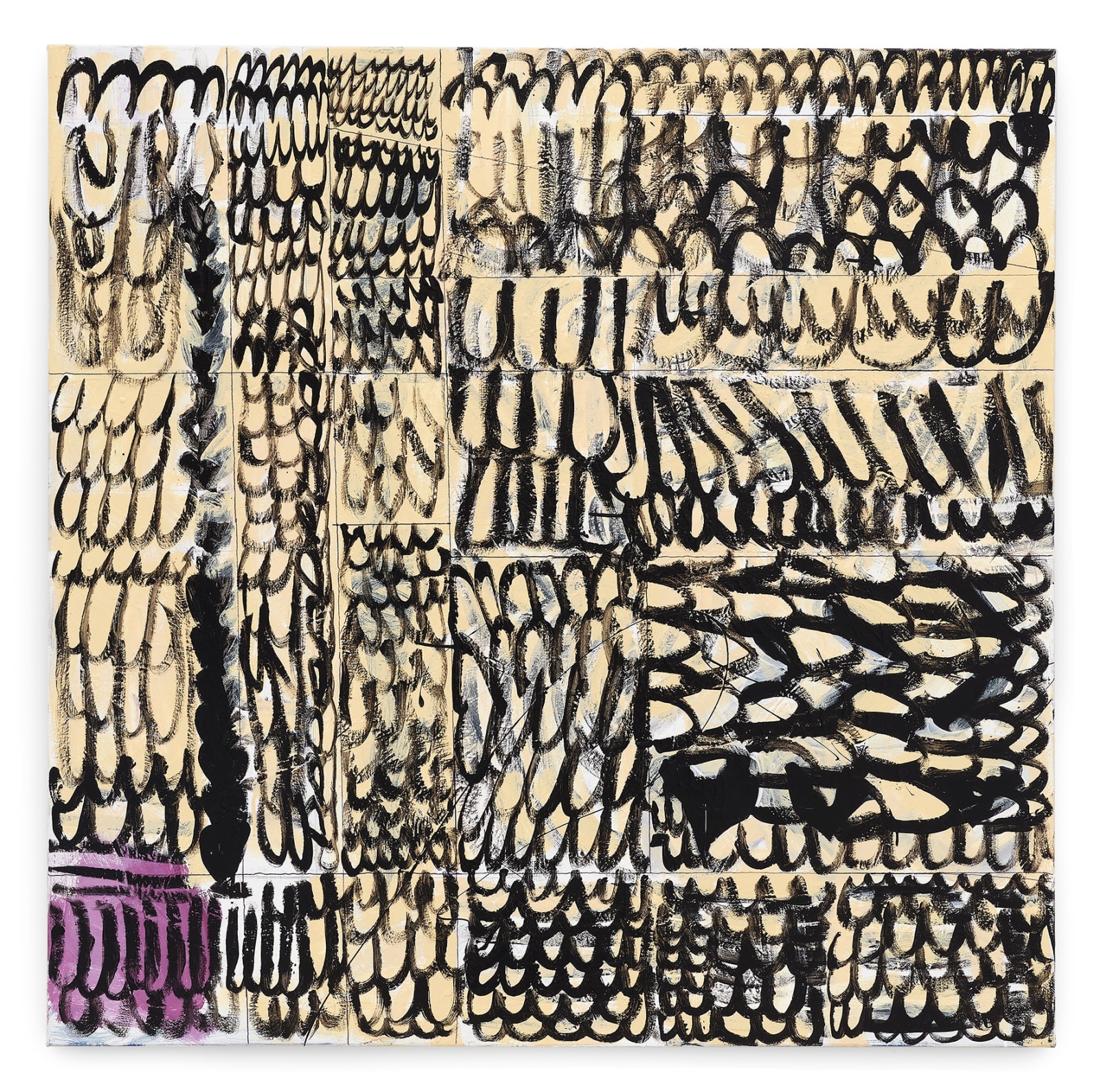

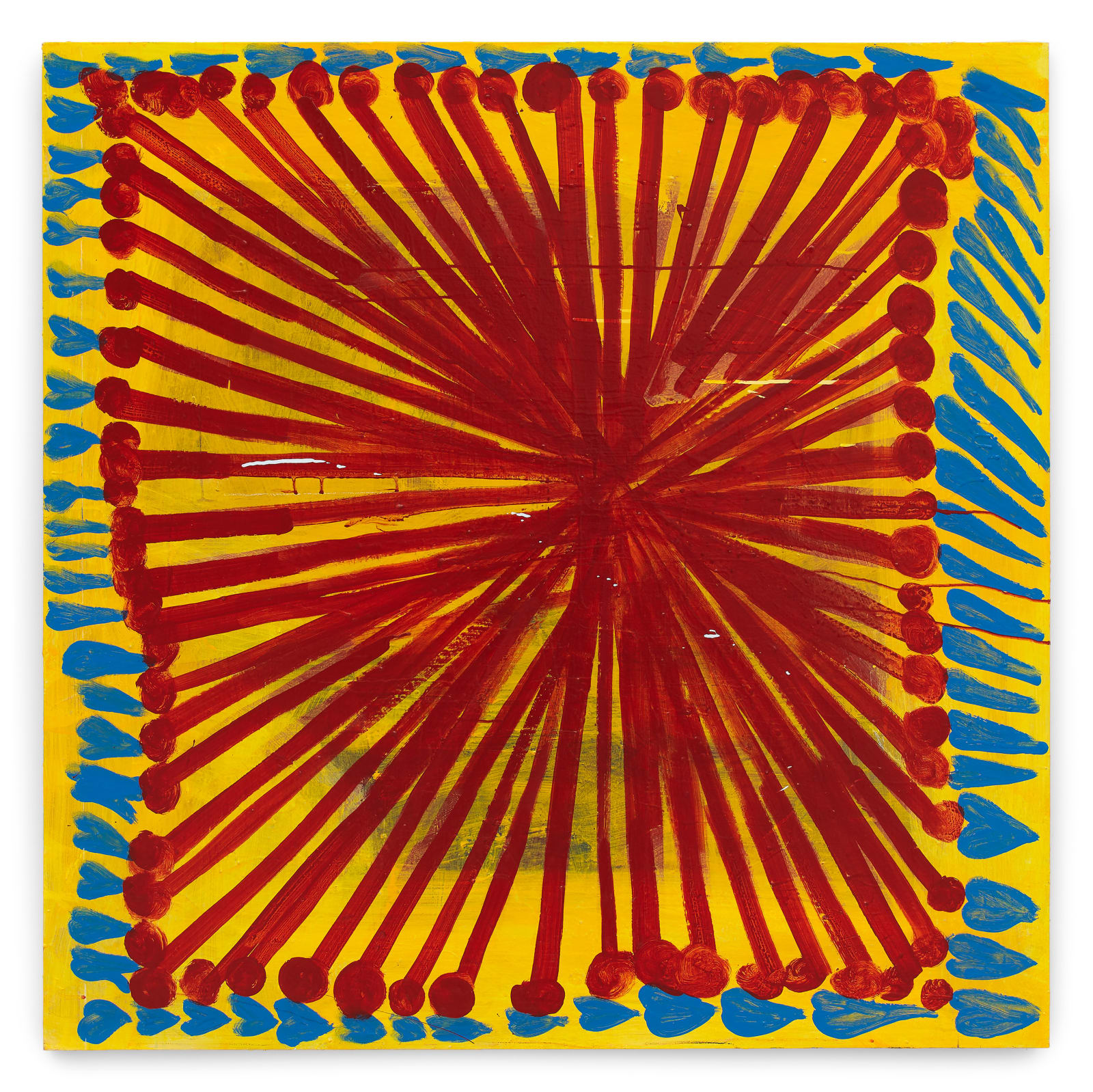

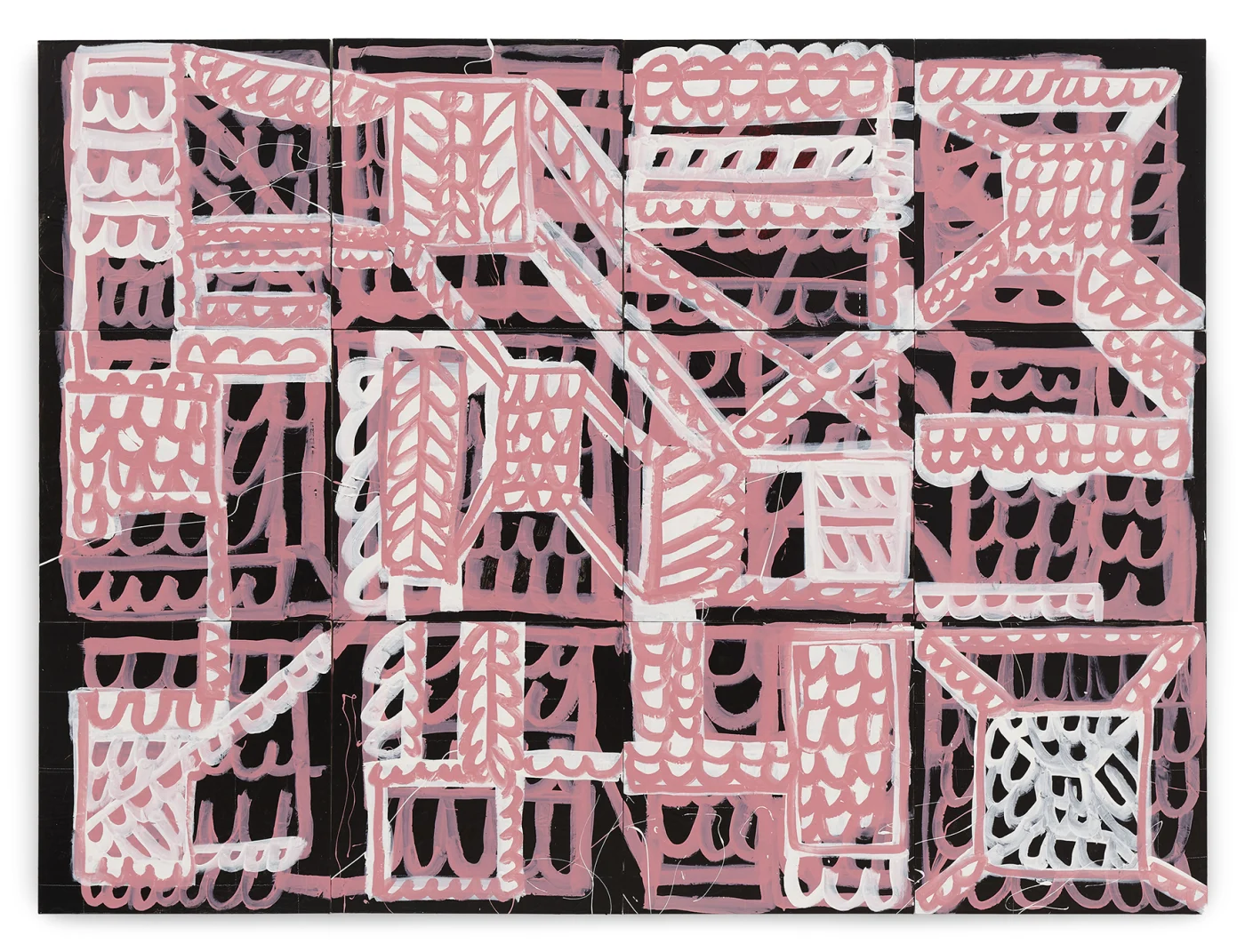

Formal play typifies Glick’s practice; her paintings juxtapose repeated segments of line with gestural marks. Both experimental and complex, Glick’s style demonstrates her continued interest in the universal language of abstraction.

Stephen Friedman Gallery presents two solo exhibitions by American artist Pam Glick for Independent and Frieze New York. The presentations, which will take place one week apart in New York, are both curated by Matthew Higgs, Director of White Columns, New York and Founding Curatorial Advisor of Independent.

Formal play typifies Glick’s practice; her paintings juxtapose repeated segments of line with gestural marks. Both experimental and complex, Glick’s style demonstrates her continued interest in the universal language of abstraction. The artist uses calligraphic pencil marks to disrupt the paint, contrasting with the structured grid of the canvas. Layers of mark-making lend a cartographical aspect. Speaking of her painting process, Glick says, “I think of it as a playground that I set up.”

An overview of Glick’s recent practice is exhibited for Independent. The artist organises the sections in her paintings to possess rhythm, creating a visual contrast between movement and stillness. A significant motif reflecting this is what Glick refers to as a ‘zip’. The artist is drawn to edges and explores the ways in which space is divided and contained. This is conveyed in how Glick incorporates strong, centralised and vertical lines among free-flowing forms, creating a physical viewing experience.

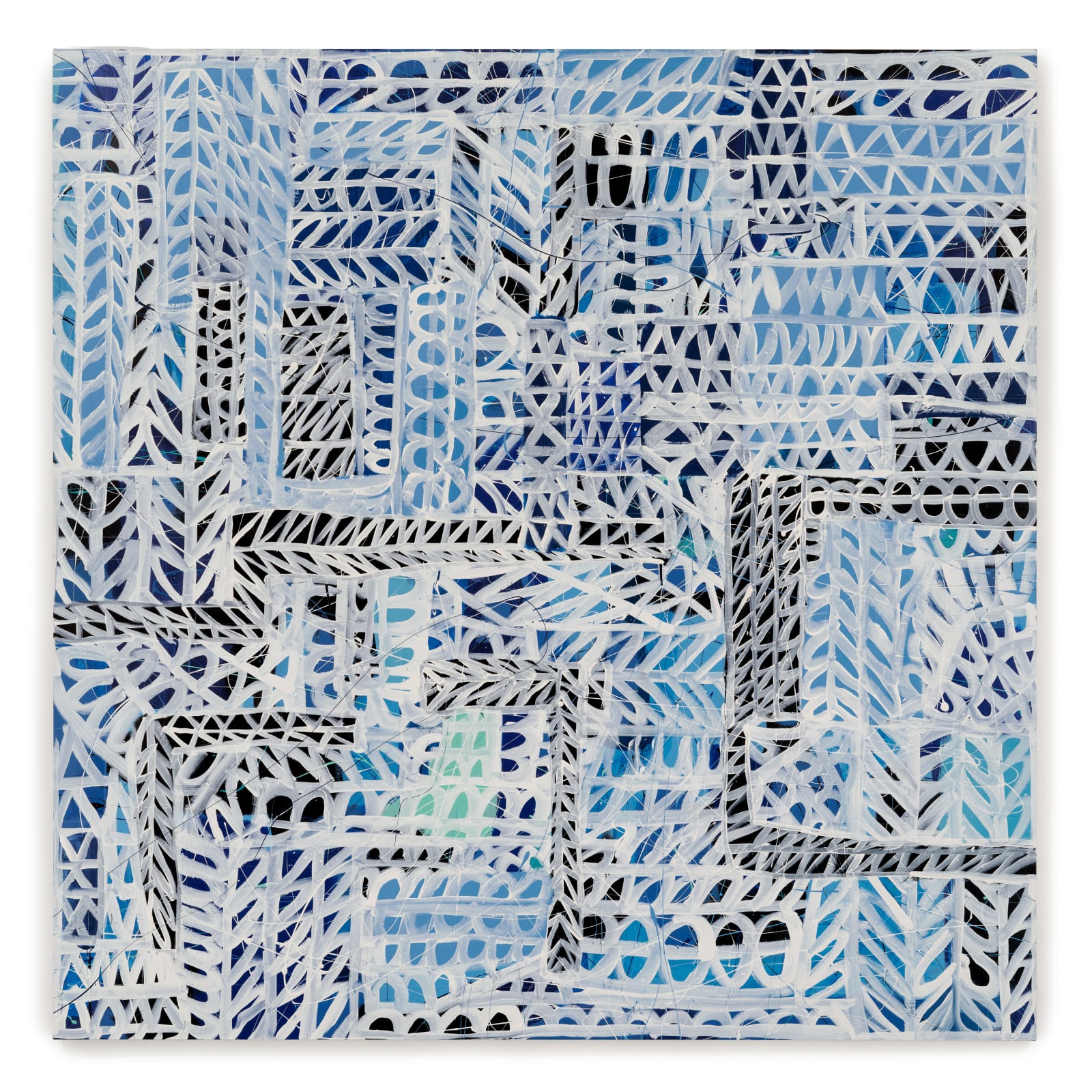

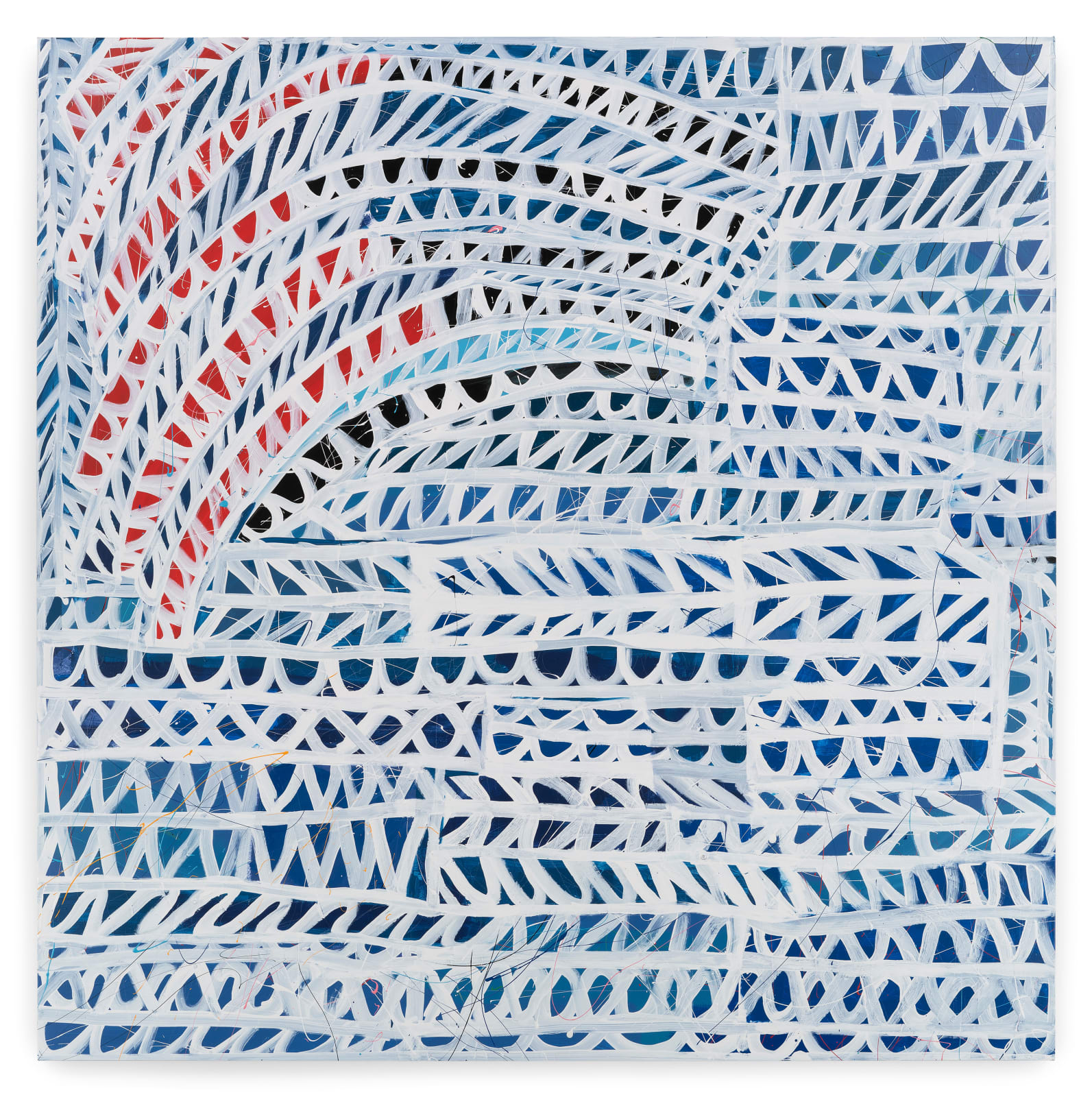

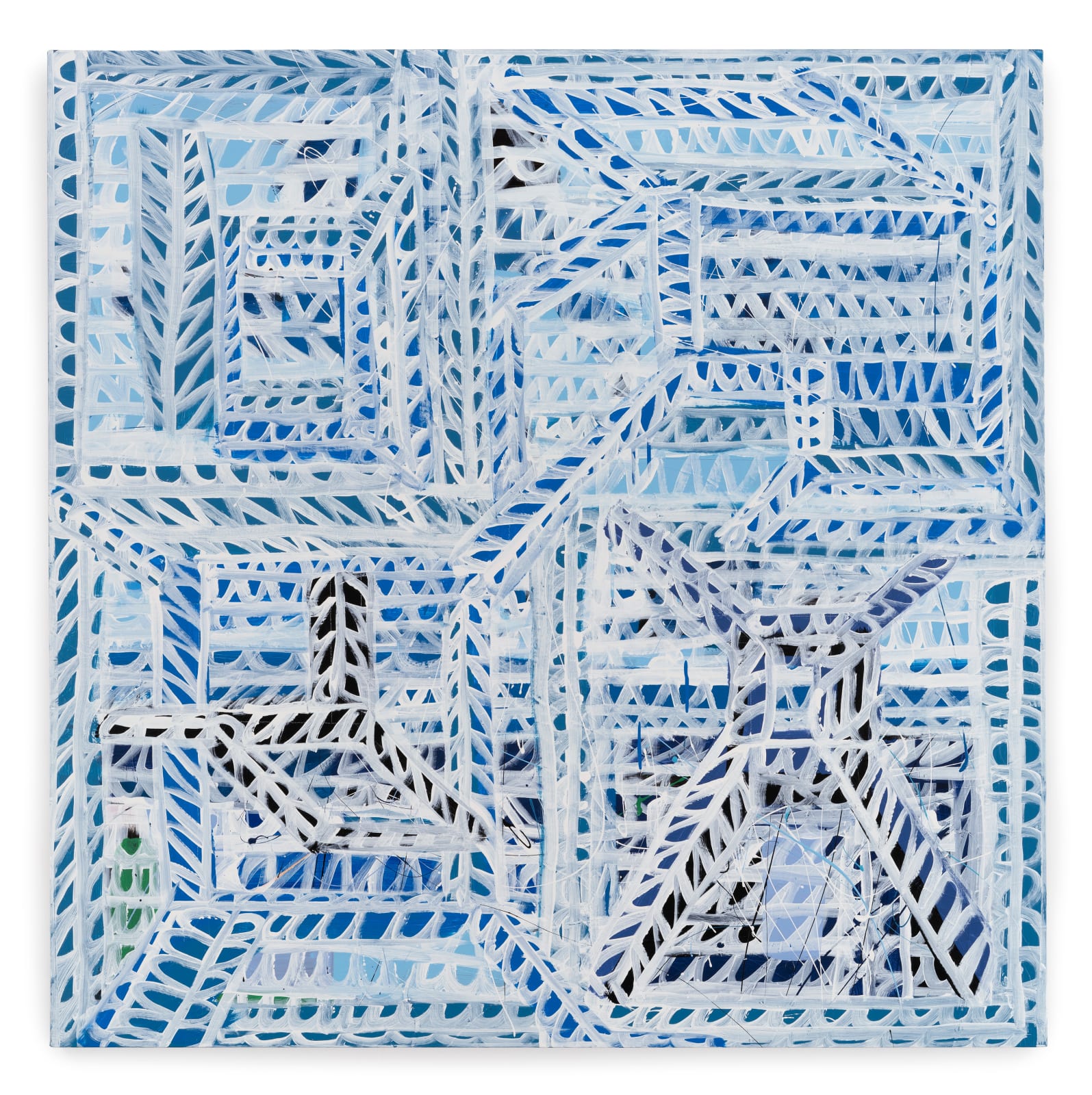

For Frieze New York, a series of new paintings titled ‘Box of Rain’ is exhibited. Working predominately in blue and white, the paintings evoke cresting waves or the formation of rainfall during a heavy storm. Although abstract, they are informed by the location in which they are created, absorbing the energy of that place and channelling it towards the viewer. Glick, whose studio is located close to Niagara Falls, refers to the ubiquitous connection between water and abstraction; “Every abstract painting looks like some sort of depiction of water falling.” The artist’s paintings pull between straight line and expressive curve as she reflects water’s unruly nature within the canvas.

Alongside Niagara Falls, Glick also cites Diego Velázquez's ‘Las Meninas’ as a source of inspiration. The dresses worn by subjects in Velázquez's painting depict flatness and falling in a similar manner to the flow of a waterfall. Despite the simplified forms within her works, Glick’s compositions are free yet detailed, and possess a depth which is seemingly psychological.

Featured below is a short film of Pam Glick working in her studio and an interview between the artist and Matthew Higgs, Director of White Columns, New York and Founding Curatorial Advisor of Independent

Pam Glick - In the Studio

Pam Glick in Conversation with Matthew Higgs

Matthew Higgs: A recurring subject of your work is the Niagara Falls, which lie on the American-Canadian border close to Buffalo, where you live and work. Can you say something about your relationship with the Falls, and how you first came to create images of them?

Pam Glick: When I was growing up my father had a lot of out-of-town clients who came to visit him in Buffalo. There were always trips to Niagara Falls to show off the great spectacle. I always volunteered to go along, as it was the one true wonder of the world that I had seen and never got tired of seeing. From downtown Buffalo, where my father’s office was, you could see the mist from the Falls, which were twenty miles away – it was always the first thing that I looked for when I went to visit him at work. The Falls themselves are violent and majestic, and they are still awe-inspiring every time I return there.

The other significant cultural influence in Buffalo was the Albright-Knox Art Gallery. My grandmother Dottie used to take me there regularly as a child. We would look at and talk about the paintings together. I remember her asking me about Jackson Pollock’s ‘Convergence’, 1952. I said that it looked like the Niagara Falls to me – I would have been around nine years old at the time – and that prompted her to tell me about the meaning of the word ‘abstract.’ The other piece that we discussed at length in those early years was Lucas Samaras’s mirrored space ‘Room No. 2’, 1966. Standing inside that sculpture, Dottie introduced me to the concept of infinity. Those two works were in pretty close proximity to one another in the museum and I always connected them in my mind as being one idea. We always had to see one and then the other.

After graduating from art school in 1980, I found myself back in Buffalo living with my parents once again, waiting to move to New York City. I was painting in their basement and I thought it would be interesting to paint a triptych of the Niagara Falls. I submitted this early work to the Albright-Knox’s ‘In Western New York’ biennial and miraculously, it was accepted. So, my first exhibited work was actually a painting of Niagara Falls. It was installed at the Albright-Knox directly upstairs from the Pollock and Samaras’s mirrored room.

Overview

Matthew Higgs: Waterfalls are, by their nature, in a constant state of flux – chaotic and entropic. I once suggested that your depictions of the Niagara Falls operate as visual metaphors for both the inevitability of change and for the potential of renewal; that your paintings ultimately suggest a form of psychological and emotional mapping. Is this still a reasonable way to think about or to interpret the work?

Pam Glick: Yes. In fact, I have quoted you many times! The waters at the Niagara Falls are constantly in motion. It is an endless and perpetual cycle. Paintings with no beginning and no end are my idea of great art. A question people often ask artists is: “how do you know when the work is finished?” I am not looking for a specific answer within each painting. On the contrary, I am searching for new answers to the same questions. When a painting is in progress, it invariably moves through different stages: from being a chaotic tangle – where I often have feelings of despair, thinking that I’ll never get there and that I’ll never make another great painting – to, somehow, being ‘finished.’ This denouement is both a surprise and relief. The work itself is often possessed by an air of inevitability; almost a self-conscious sense of itself and its resolution, where the jumble of parts has settled down to become a painting.

Painting isn’t so much a metaphor for life but a mirror. There is often a feeling in real life of how precarious everything is. I tend to be optimistic, otherwise I’m not sure I could have continued as a painter for this long. I want my work to reflect upon this and to show both the possibilities and potential for renewal. It’s a lot to ask of a painting, but for me the best paintings provide a life force to those who are searching for it.

Matthew Higgs: You have always made drawings. They aren’t necessarily studies or ‘rehearsals’ for subsequent paintings, but often autonomous works in their own right. Can you say something about the role that drawing plays in your practice, and perhaps elaborate on the almost ‘calligraphic’ way that you approach painting?

Pam Glick: Drawing is where you can see everything. There is a commitment in my drawings that I hope to keep hold of in the paintings. By that, I mean that the most original and authentic responses happen in drawing. When I’m working on a large-scale painting, my goal is to approach it in the same way as when I draw. As a child I drew in the margins of every schoolbook I ever had. Nowadays, when I find myself becoming too self-conscious, I imagine that I’m back in school and I can immediately slide back into that spontaneous drawing world that I find so inspiring. The paintings now, in many ways, resemble some of the seventh-grade drawings that I made in my math books. It took me a long time to realise or recognise that those childhood drawings were in fact my mature paintings, albeit in an ‘infant’ stage.

Overview

Matthew Higgs: Your recent paintings – especially when seen together or in series – seem to me to be ‘performative’. In their scale – the majority are 72 x 72 inches – there appears to be a direct correlation to the body and to the physical limits of the body?

Pam Glick: This makes sense because the paintings demand a degree of athleticism to make. I was athletic as a child and equate making art to physical movement. Like when you are running through the woods in cross country and you are focused on your footfall, whilst also watching the path ahead. That’s a good road map or an analogy for painting. Sports saved me from being expelled from school and art saved me in a similar way. Painting, for me, is the place to be most present – physically, psychologically and emotionally.

Matthew Higgs: Your paintings – self-consciously – resonate with multiple and overlapping art histories. They align a lyrical sensibility akin to Brice Marden’s organic paintings of the 1980s, for example, with a more ‘attitudinal’ approach to painting that we might identify with, say, graffiti or with the work of artists as different as Mary Heilmann or Chris Martin. How do you negotiate art history in your work?

Pam Glick: The artists you mention are some of my favourites. I have a voracious appetite for looking at art, old and new. For example, when I first saw aboriginal painting, it was initially disconcerting because some of it looked a lot like my work at the time. I thought a lot about how that happens. I’m interested in this ongoing process of influence, and being influenced. When I encounter a great work or art, one that speaks to me, I see it as a kind of ‘permission’ – an invitation, an open door to go through and explore what lies beyond, to learn from the experience of the encounter. I’m interested in the thresholds between different cultures and how the connections might resonate within my work: When you feel that ‘call’ from another artist’s work, just as they had felt moved by a different artist’s work, and so on. The greatest thing about painting, for me, is that it is an ongoing conversation across time.