Melvin Edwards: Brighter Days

Overview

"Edwards has chosen to title the exhibition 'Brighter Days', suggesting that while we remain mindful of the past, we must also look to the future with optimism." – Daniel S. Palmer (Curator, Public Art Fund)

For more than 60 years, Edwards has created works that bring abstract forms together with recognisable motifs—often related to his own personal history—to engage with themes of race, labor, and the African Diaspora. Each of the six sculptures includes some type of chain—a form that Edwards has long engaged with and that may suggest oppression but also liberation and connection. The first thematic survey of his public sculpture, Brighter Days offers a focused look at the development of his work, revealing both its originality and contemporary impact.

“Over his long career Melvin Edwards has developed a singular sculptural language that melds large-scale abstraction with personal imagery and socially resonant themes. This exhibition brings together five key historical works with a new commission to explore the artist's use of the chain motif over some fifty years," says Public Art Fund Curator Daniel S. Palmer. "Often connoting oppression or brutality, the chain link also symbolises connection and, especially when broken, liberation. Edwards has chosen to title the exhibition Brighter Days, suggesting that while we remain mindful of the past, we must also look to the future with optimism.”

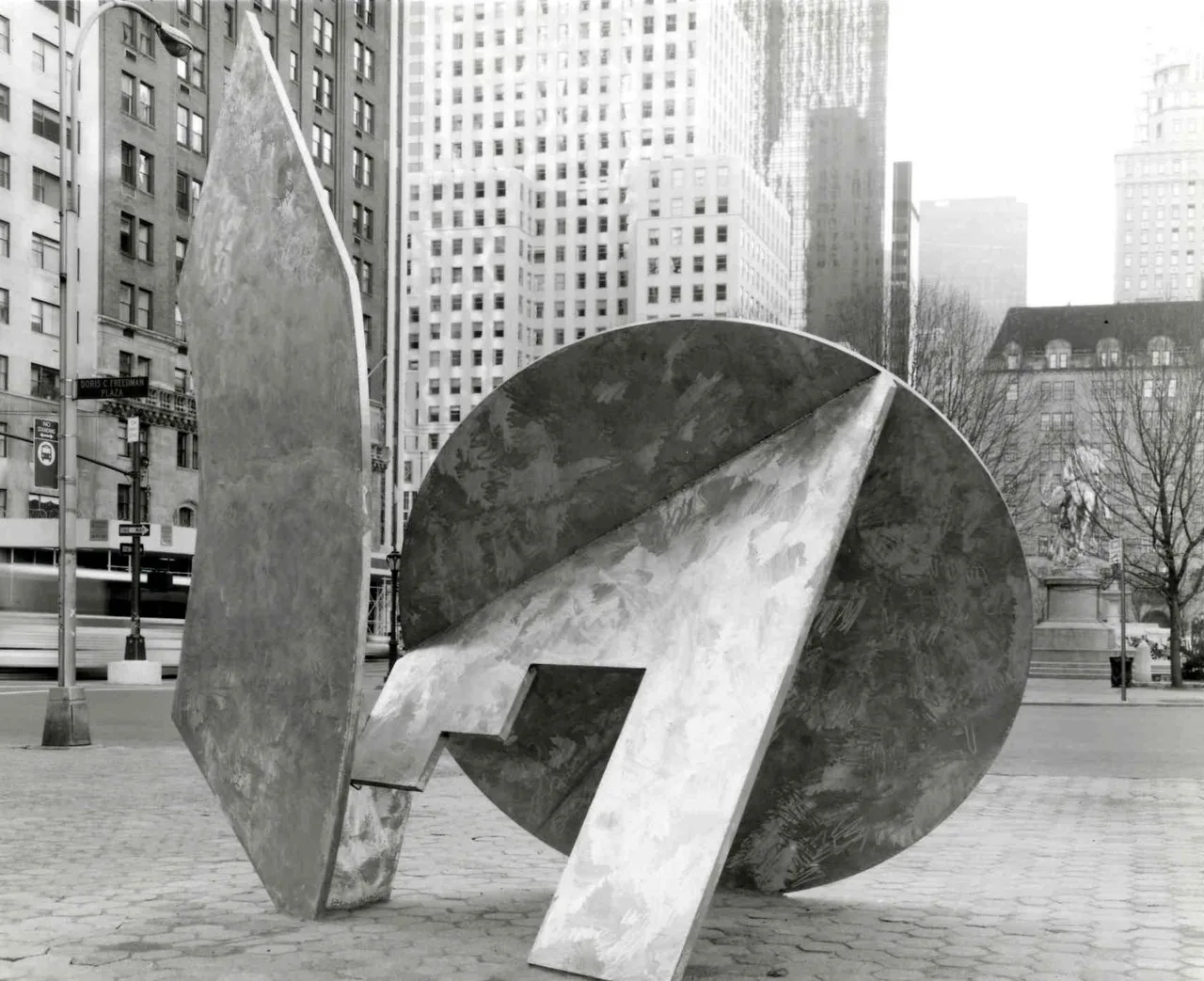

In 1970, Melvin Edwards was the first Black sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and his wall-mounted works, in particular those from his powerful Lynch Fragment series, have been featured in significant museum exhibitions across the country—including in the New Museum’s current exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America. Public Art Fund first showed Edwards’ work, Tomorrow’s Wind, at Doris C. Freedman Plaza, Central Park in 1991. Currently on permanent view at Thomas Jefferson Park in East Harlem, it is one of four large-scale sculptures by Edwards that can be seen in New York City. 30 years later, Brighter Days explores his boundary-breaking public art practice and several recurring key themes in his work, primarily the chain motif. This form—as well as the rocker, which is featured in several works—carries deep personal symbolism and speaks to the experiences of Black communities in the United States. Edwards uses chain links in different formal iterations, melding abstraction and symbolism to imbue his sculptures with layers of meaning. Connected links may suggest oppression but also the interconnections between generations and communities, while the broken chain is evocative of both rupture and liberation.

Homage to Coco (1970) is the earliest work in the show. The first of Edwards’ sculptures to explore the rocker motif, it features a steel frame with suspended chains that suggest lightness and movement. The title refers to the artist’s grandmother and her rocking chair, connoting domesticity and the space of the African American home. The symbolism galvanises the personal meaning of the piece, while also broadening its association with the transmission of culture through storytelling.

The four other historic works in Public Art Fund’s survey exhibition continue to explore major themes seen throughout the various eras of Edwards’ career, in which he reflects on the history of race, activism, and the African Diaspora in the United States. The Promise (1984), Before Words (1990), Ukpo. Edo (1993/1996) and Untitled (1993)—all part of Brighter Days—elaborate and expand on the dominant motifs first established in earlier pieces such as Homage to Coco. The powerful element of the chain appears in the newly commissioned Song of the Broken Chains (2020), a work that Edwards has created for Brighter Days. Like many of the historic pieces, the large-scale sculpture implies both oppression and connection, both literally through imagery of chains, but also physically in their larger-than-life size. The six sculptures draw powerful symbolic connections to both the history of slavery and freedom, and engage an important conversation with the context of the exhibition site. In the 1700s, City Hall Park was an African burial ground and the site of the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence. In the summer and fall of 2020 it was the site of Black Lives Matter protests and the occupation of City Hall. This May, Brighter Days will celebrate Edwards’ unique, powerful, and timely sculptural vocabulary and create space for connection, dialogue and hopeful reflection.

'Brighter Days' was previosuly on view at City Hall Park, New York City, New York, USA.

Text from Public Art Fund's Press Release.

"Edwards has chosen to title the exhibition 'Brighter Days', suggesting that while we remain mindful of the past, we must also look to the future with optimism." – Daniel S. Palmer (Curator, Public Art Fund)

Installation Views

"Just like the tilted rocker with its stored potential for motion, Edwards' … [materials] are teeming with the potential proliferation of meaning. By paring down these objects to their most simple elements and melding them into new configurations, Edwards presents viewers with these forms before any single interpretive regime can solidify them.”

– Tobias Wofford (Writer, Art Historian)

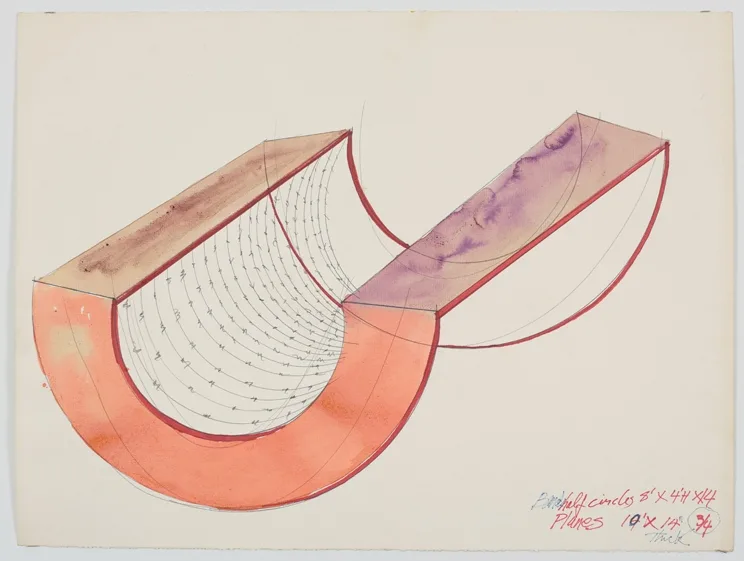

'Homage to Coco' and ‘Before Words’ are crucial examples of the pioneering artist’s celebrated ‘Rocker' series. This body of work was inspired by a rocking chair that belonged to his grandmother Coco, on which Edwards recalls injuring himself whilst playing as a child. The sculptures rest each rest on a base of two hemispheres and perform a delicate rocking motion when pushed. The tenuous balance of the 'Rockers' evokes feelings of precarity and alludes to the artist’s broader childhood experiences, living at his grandmother’s house in the violent Fifth Ward of Texas during segregation. The steel’s robust quality is countered by the sculptures' graceful form, while the sound of grinding metal that accompanies their ponderous motion reinforces the materials’ industrial associations.

‘Homage to Coco’, 1970 is the first of Edwards’ 'Rocker' series, which he initiated as an alternative to the kineticism explored by Jean Tinguely’s mechanised sculptures and Alexander Calder’s mobiles. While Edwards' formal language clearly engages with the history of abstraction and modern sculpture, his work is born out of the social and political turmoil of the civil rights movement in the United States. Referencing African traditions of blacksmithing and the physical bondage of slavery, the chains in ‘Homage to Coco’ and ‘Before Words’ also function as a symbol of kinship and continuing tradition. In an interview with the curator Catherine Craft, Edwards reflects that such “contradictions, or contradistinctions are things that have occupied me in visual art.” Activated by the tensions inherent in their construction, these sculptures evoke ongoing historical battles between resistance and oppression.

“When I rocked it, because the chain was flexible, it lagged behind in terms of movement. [...] If there were no chain there, it would just act like the normal pendulum until it got tired of rocking, and it would stop. But the chain, it gets to that position and it goes back. … So I said, whoa, the chain syncopates the motion of the rocker! … And I use the word with a sense of sensitivity to syncopation used in relation to African American music, as an emphatic quality.”

– Melvin Edwards

"I have always understood the brutalist connotations inherent in materials like barbed wire and links of chain and my creative thoughts have always anticipated the beauty of utilizing that necessary complexity which arises from the use of these materials in what could be called a straight formalist style."

- Melvin Edwards

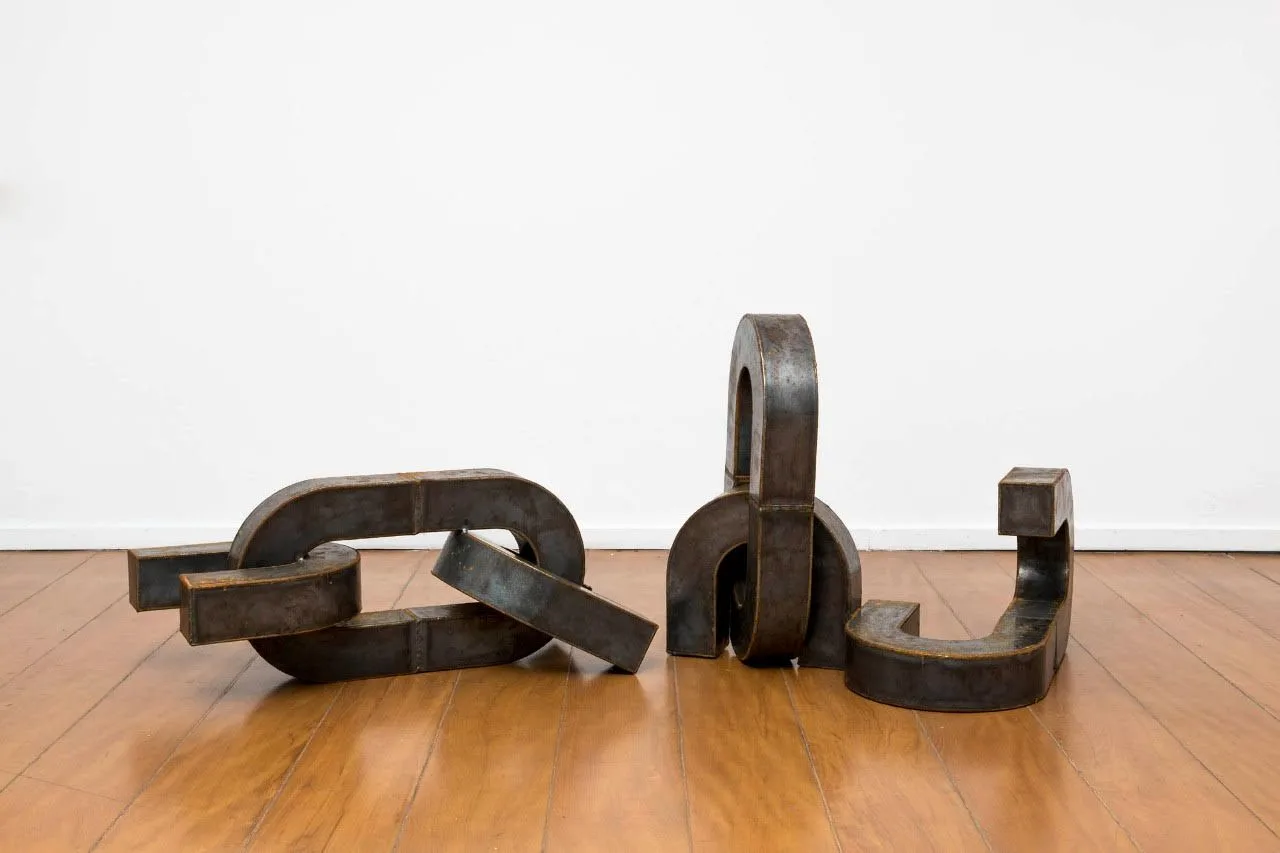

Created specially for 'Brighter Days', ‘Song of the Broken Chains’ 2020 represents a significant development in the series of chain-based works that Edwards initiated in the early 2000s. Whilst the majority of these sculptures feature upright columns of forged links, here the artist presents a trio of shattered chains scattered on the ground. Edwards employs the form of a broken chain to invoke emancipation from imprisonment and slavery but also to signify lost kinship. A symbol of alienation as well as freedom, this work speaks to the ideas of historical erasure and restitution within the context of the African Diaspora. Embracing multiplicity and eschewing singular interpretation, this work explores ongoing battles between resistance and oppression.

“Human beings are chained to their existence psychologically, economically, physiologically—all kinds of ways. The breaking of chains produces many other possibilities.”

– Melvin Edwards

This exhibition marks the first time that ‘The Promise', 1984 has been viewed publicly since the early 1990s. The shimmer of the wire-brushed stainless steel is emblematic of a number of Edwards’ large-scale works on permanent view throughout New York City, including 'Passage', installed on the campus of Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn. The work belongs to a series of large-scale sculptures created by Edwards in the 1980s and shares its basic structure with ‘Gate of Ogun’, now in the collection of the Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York. Here the artist adapts the triumphal arch, a distinctive architectural form associated with ancient Roman rituals of commemoration. Constructing one column as a vast chain, Edwards transforms this archetype of imperialism into a symbolic gateway to socio-political emancipation.

“If [the sculptures] are the right scale […] a person will be able to experience them the way they experience architecture—that is, they move through and around and have a different visual experience from every point of view of the piece. But even the forms that make up the symbols will be visually interesting and change from one point of view to another and do different things in space.”

– Melvin Edwards

A dynamic arrangement of graphic forms, ‘Ukpo. Edo’, 1992/ 1996 reveals Melvin Edwards’ expressive and intuitive approach to art making. Alluding to the southern Nigerian state of Edo, the sculpture can be read as a reimagined cityscape. When Edwards began travelling to Nigeria in the 1970s he often visited Benin, where the Yoruba region stimulated his interest in architecture and urban design. The artist's free method of composition is infused with African sculptural traditions of experimentation and innovation. Edwards discovered in Africa what he described as the “corroboration of generations feeling a similar need to create something new and different.”

Combining the rough-hewn physicality of industrial steel with abstract formal composition, 'Untitled', 1993 demonstrates the expressive complexity that Edwards draws from his signature materials. The rhythmic play of sharp angles and broad curvilinear planes invites the viewer to walk around the structure. The polished metal captures and reflects the natural light, recalling earlier public sculptures such as ‘Southern Sunrise’, 1983 at Winston-Salem State University in North Carolina that also feature circular forms. Exploring historical experience within the context of the Diaspora, these sculptures are oriented Eastward towards both sunrise, Edwards explains and African continent.

Melvin Edwards is a pioneer in the history of contemporary African-American art. Edwards is celebrated for his distinctive sculptures and three-dimensional installations created from welded steel, barbed wire, chain and machine parts. Themes of race, protest and social injustice permeate the artist’s practice. Edwards' career began in southern California with a solo exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 1965. In 1970, Edwards went on to become the first African-American sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, presenting a ground-breaking installation of work made from barbed wire.

Edwards' work currently features in the new hang of the collection at MoMA, New York. His work was included in the landmark touring exhibition ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power', initiated by Tate Modern in 2017. In April 2020, the artist exhibited at Glasgow International in Scotland. Edwards was recently awarded the prestigious US Artists Fellowship 2020. Edwards' works are featured in many prominent collections internationally including Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California, USA; Museum of Fine Arts, Texas, USA; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., USA; Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, USA and Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York, USA.