Mira Schendel in conversation with Max Bill, Naum Gabo, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, Roman Opalka & Bridget Riley

Overview

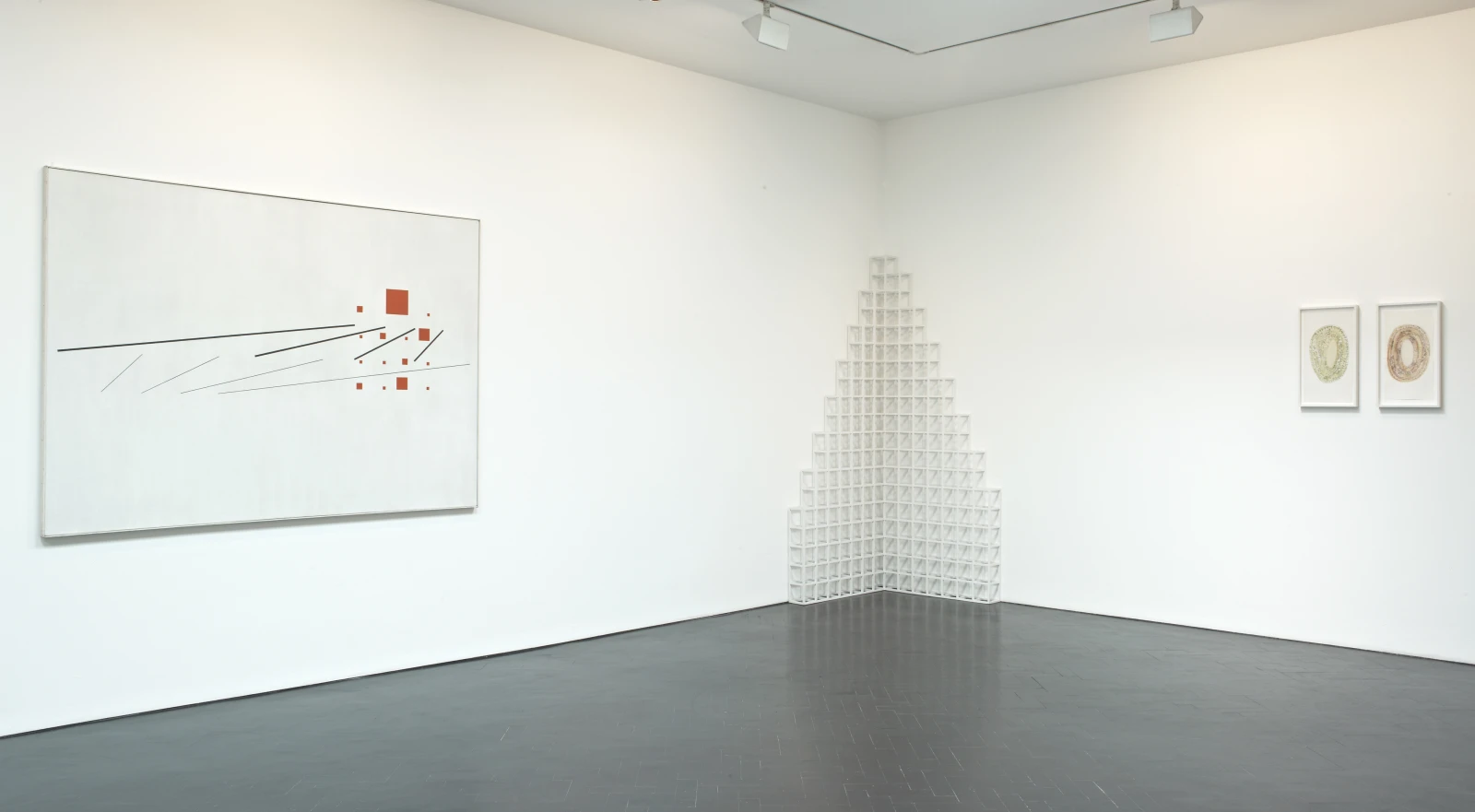

The sculptures, paintings and works on paper presented here provide ways of looking afresh at the breadth of Schendel’s practice.

Stephen Friedman Gallery is delighted to present Mira Schendel in conversation with Max Bill, Naum Gabo, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, Roman Opalka & Bridget Riley. Mira Schendel is recognised as one of the most significant Latin American artists of the late 20th century. Her work, which encompasses a broad range of media, is underpinned by a philosophical and spiritual interest in the formal properties of language.

Under Schendel’s hand - one undoubtedly shaped by the persecution and political unrest so prevalent in the first half of the 20th Century - language is presented not just as a communicative device, but rather a wider visual metaphor for human existence.

Stephen Friedman Gallery is delighted to present Mira Schendel in conversation with Max Bill, Naum Gabo, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, Roman Opalka & Bridget Riley.

Mira Schendel is recognised as one of the most significant Latin American artists of the late 20th century. Her work, which encompasses a broad range of media, is underpinned by a philosophical and spiritual interest in the formal properties of language. Under Schendel’s hand - one undoubtedly shaped by the persecution and political unrest so prevalent in the first half of the 20th Century - language is presented not just as a communicative device, but rather a wider visual metaphor for human existence.

The works by Schendel presented here include rare examples of her paintings, drawings, monotypes and examples from the Dactiloscrito series. Together, they illustrate the varied and on- going fascination that the artist held with the linguistic form.

The monotypes were produced in the 1960s and considered most experimental for their time. They were made by pressing talcum powdered Japanese tissue against pre-oiled glass sheets, with Schendel creating forms by ‘drawing’ or applying pressure on the unoiled side. The artist insisted that the finished drawings were shown suspended and encased between two sheets of Perspex. As

such, the gestural marks, handwritten words and phrases appear to hover in space, freeing the written word from the constraints of its two dimensional plane. Elsewhere, the repetition of Letraset transfers on paper and stencilled letters on canvas continues the artist’s endeavour to stretch language to the very limits of its meaning and use.

The multi-national group of artists brought together here in conversation with Schendel, share a similarly considered approach to art making. Inspired by the intellectual debates that characterised much of the mid 1900s, particularly the emergence of semiology as a field of study, these artists evoked numerous media to explore and attempt to understand the rapid social change unfolding around them. Their common mode was largely abstract in form, with colour and considered mark-making providing the apparatus with which to articulate a keen conceptual awareness.

The sculptures, paintings and works on paper presented here provide ways of looking afresh at the breadth of Schendel’s practice. Repetition of form, particularly within a minimalist aesthetic, is particularly prevalent in her work and can be observed just as keenly elsewhere. ‘Disturbance’ by Bridget Riley, shows a stark white canvas on which an oval form is repeated at various angles. This painting, a keen example of Riley’s endeavours to challenge the very act of seeing, is particularly notable for the emotional tension created in the title, a device not oft used by the artist.

Repetition is equally dominant in ‘Detail 5558756 - 5564164’ by Roman Opalka. Opalka’s life’s work was centred around one task: ‘the description from number one to infinity’. Each of his paintings list row after row of hand written numbers, on muted backgrounds. Each canvas was identical in size and Opalka’s process was rigorously controlled by self-imposed rules. As such the artist’s practice was defined by its adherence to a strict system.

Agnes Martin, another female artist whose work was of significant influence on the field of minimalism, is represented here by one of her early oil and ink on linen paintings. The fields of colour, which appear to float on the surface of the linen, subtly draw attention to Schendel’s use of colour planes in her own paintings.

‘Simultaneous Construction of 2 Progressive Systems’ by Max Bill is another painting that evokes the spirit of both minimalism and geometric abstraction. Here, bursts of orange colour are rigidly constrained into regular squares that rest against diagonal striations of varying thicknesses. This large-scale and beautifully preserved example of Bill’s painting clearly illustrates the multitude of interests inherent to his practice, including art, design, architecture and typography.

Elsewhere, sculptures by Naum Gabo and Sol LeWitt further illustrate the artistic endeavour to translate concept into abstract form. LeWitt’s ‘Untitled’ is one of his later ‘structures’ – the artist’s term for his sculptural work. It lays bare the skeleton of the cube and in doing so offers a moment to contemplate the shape so pivotal to much of his practice and indeed the shape that influenced much of his own personal theory of visual signs. The linearity of this work also brings to the fore the use of the line in many of Schendel’s later paintings.

Gabo’s ‘Construction in Space with Crystalline Centre’ is one of the finest examples of the artist’s juxtaposition of the organic and the precise. The undulating Perspex exterior provides a transparent framework through which to view the central crystal form. As such, there is the possibility for an infinite number of perspectives of the work.

An absorption with transparency became equally important to Schendel over the years. Her own use of Perspex became more pronounced as she endeavoured to offer a multitude of viewpoints and meanings to be taken from her work. From the presentation of her monotypes through which the translucent nature of the rice paper was highlighted, to the sculptures from her Cadernos series where rice paper was sandwiched between acrylic leaves, Schendel was engaged in a constant battle to free her work from the constraints of its two dimensional surface.

This concern extended to the exhibition of her work, with Schendel often giving instruction for pieces to be hung in front and on top of one another, leading to a layering of both imagery and meaning. It is therefore fitting that ‘Mira Schendel In Conversation’ brings together work by numerous artists whose work championed similar beliefs.

The exhibition as a whole aims to provide a small snapshot of art history, bringing together like-minded artists whose personal narratives still manage to traverse a wide breadth of time and place. All shared an aim to free art from the realm of realism and to instead imbue it with the utopic ideal of appealing to the conceptual rather than the physical.

From Minimalism to Conceptualism and Abstract Expressionism, the work presented here brings to the fore the wide range of contexts prevalent within the reading of Schendel’s practice.

The sculptures, paintings and works on paper presented here provide ways of looking afresh at the breadth of Schendel’s practice.

Installation Views